Why Mindfulness?

You probably have heard people talk about the benefits of mindfulness. What many people don’t realize that mindfulness is much more than a fad or “new age-y” spiritual practice, it is also a key component to healing the symptoms of trauma, and there is LOADS of research in neuroscience to back this up.

Mindfulness has a regulating effect on the nervous system.

Deregulation of the brain areas related with emotional regulation and memory are key contributors to the symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress injury (PTSI), as well as the over activity of the amygdala, the fear centre part of the brain. Mindfulness reverses these patterns by increasing prefrontal and hippocampal activity, and moderating amygdala activity.

Mindfulness practices counteract trauma-related cortical inhibition, regulate autonomic activation, and allow us to foster interest and curiosity towards our emotions, our thoughts, our bodily sensations, and our many parts that make up the whole of who we are.

Mindfulness is awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally, [in the service of self-understanding and wisdom]”, says Jon Kabat-Zinn, American professor emeritus of medicine and the creator of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Mindfulness facilitates the capacity for “dual awareness” or “parallel processing” allowing one to explore the past without risking re-traumatization by keeping one “foot” in the present and one “foot” in the past (Ogden et al., 2006). This is often crucial for individuals contending with debilitating flashbacks to know – fear of re-traumatization is usually the very thing that keeps people from seeking therapeutic support.

Many traumatized individuals are extremely uncomfortable with bodily sensations, so a suggestion of cultivating a mindfulness practice isn’t exactly welcomed. I totally get it, and there is no need to go into self-criticism that you “should” be comfortable with mindfulness. Here’s why: There is a phenomenon referred to as “bottom-up hijacking” which is an extreme form of bottom-up processing where activation of the limbic system (particularly the amygdala) in response to trauma-related cues causes the prefrontal cortex to shut down and the limbic system to go into overdrive (van der Kolk, 1998). Bottom-up hijacking is akin to a smoke alarm going off when you just turn your oven on high – it is not providing accurate information and causing alarm when no real threat is present (neither the smoke detector or your prefrontal cortex is receiving an accurate story of what’s going on – it is being hypervigilant).

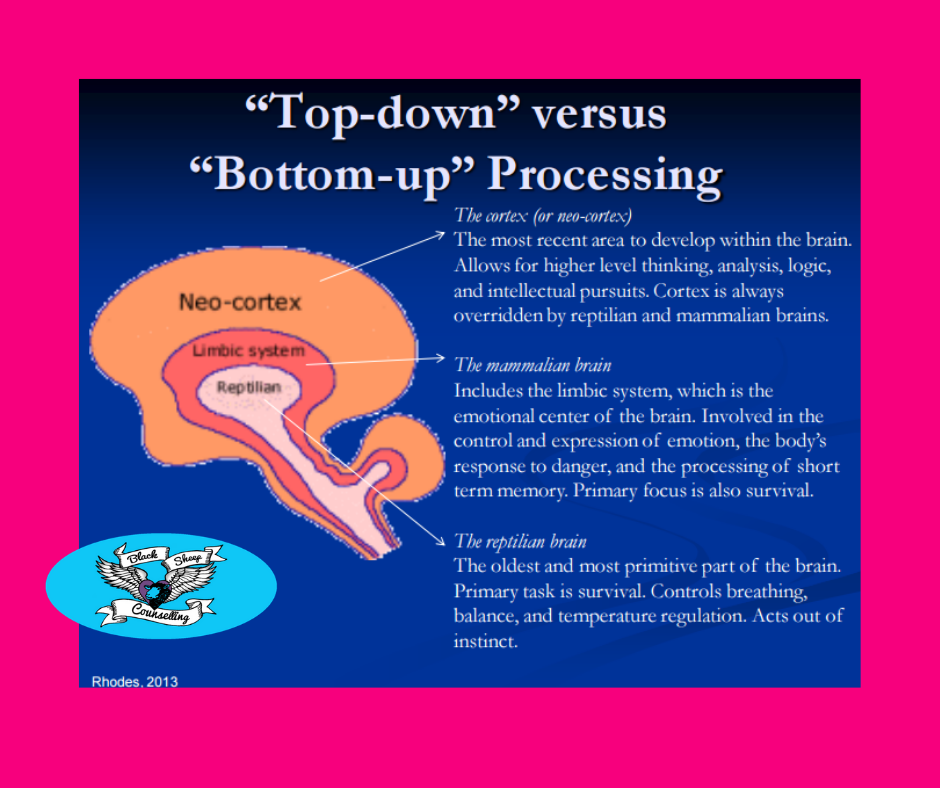

For the many trauma survivors who contend with bottom-up hijacking, the most effective way to reduce trauma symptomology is by embracing both a “bottom-up” and a “top-down” approach to treatment. Refer to the below image of MacLean’s Triune Brain Model and see that there are three distinct areas detailed. The last part of the human brain to develop is the neo-cortex. The neocortex is also known as the “mammalian brain” and is responsible for higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, spatial reasoning, and language. The neocortex is considered the “top” part of the brain and many popular therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) work from this top-down approach.

The first part of the brain to develop is the “reptilian” or primal/animalistic brain (known scientifically as the basal ganglia). The reptilian brain is located at the “bottom” and is popularly known as being in charge of the for F’s: feeding, fighting, fleeing, and…well let’s call the last one “reproduction” to avoid using the fourth f-word 😉. The reptilian brain is also responsible for the automatic bodily functions such as regulation of body temperature, the beating of the heart, and the breathing of the lungs. The reptilian brain can be thought of as the most automatic – it is part of our unconscious (subconscious) mind whose primary purpose is to stay alive and pro-create. Many of the get-you-into-trouble traits associated with the reptilian brain include aggression, dominance, rigidity, obsessiveness, compulsiveness, greed, submission and territorial behaviour. This primal part of the brain does not have the capability to learn from past mistakes and understands images and sensations, not verbal language (think how difficult it is for someone to think themselves out of a deep-seated fear of phobia – this stuff is rooted in the reptilian part of the brain). Behavioural patterns associated with the reptilian brain include defense of Self, family, personal property, and non-verbal communication/socio-normal actions such as handshaking, head nodding, clapping, and bowing.

The limbic system (the middle part), also known as the paleomammalian cortex is the emotional part of the brain and is responsible for regulating emotions and plays an important role in learning. The limbic system supports the functions of emotion, behaviour, motivation, long-term memory (specifically with the consolidation and recovery of both episodic and semantic declarative memories), and olfaction. The limbic system is essential to our survival. Diseases that adversely impact the limbic system include Alzheimer’s, Amnesia, Alexithymia, and Kluver-Bucy Syndrome.

The neo-cortex (also called the neopallium and isocortex) is the latest part of the brain to develop and accounts for 76% of your grey matter (located at the “top” of the brain). The neo-cortex is part of the mammalian brain involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, generation of motor commands, language, cognition, spatial reasoning, conscious thought, social and emotional processing, sleep, memory, and learning processes, the transmission of sensory information, and complex language processing language. The neo-cortex is what separates the human brain from the brains of reptiles whose brains lack executive functioning and cannot do much more than attend to basic functions of survival. Research in the study of neuroplasticity recently evidenced that neurogenesis (neural growth) and strengthening in the neo-cortex can happen even in adult brains – something that previously was not thought possible. Knowing that growth and healing is feasible from a neurobiological perspective, gives hope to many who struggle with mental health issues such as the common trauma symptoms of anxiety, depression, flashbacks, panic attacks, and negative self-appraisal.

So, how does one commence embracing mindfulness?

Working with a practitioner who embraces a mindfulness practice is important; we understand the workings of the brain and why commencing a mindfulness practice may be challenging. We will temper the very needed “bottom up” approach with the “top down” approach to move you towards healing in a moderated way to minimize the possibility of re-traumatization. Mindful practitioners offer their clients an open, neutral curiosity regarding organization of their experience. Through relational attunement and mindfulness-based therapies such as Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR), Sensorimotor, Somatic Experiencing (SE), Havening, and others, clients can learn to adapt to a mindful way of being through shared experience. Other tips include:

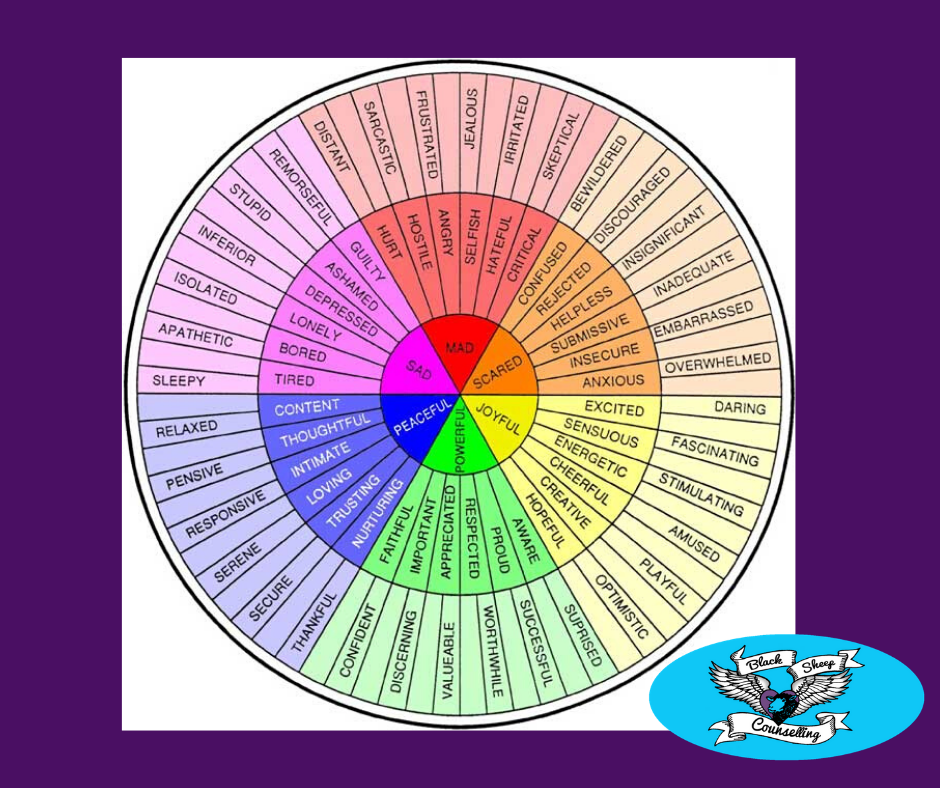

~Learn the difference between thoughts and emotion. We cannot control whether we have emotions, but we can learn to do things differently once they are triggered. When we numb, deny, suppress our core emotions they make us anxious. Depression is often anger/resentment towards another getting turned against one’s Self. Embrace curiosity when you feel a sense of “ick”. We are quick to discern we don’t like a particular emotion or sensation and often move directly into avoidance, distraction, or numbing the ickiness (byway of such things as shopping, emotional eating, gambling, drinking, Netflix binges). To effectively work towards healthy process, try to identify what the emotion is. Example: the heaviness I feel in my shoulders is overwhelm; the butterflies I feel in my stomach is anxiety. Identifying adverse emotions does not make them bigger – in fact the opposite is true: it helps us to validate them to ourselves. For more on this: https://blacksheepcounselling.com/2019/09/anxiety-turning-towards-pain/. Our entire well-being improves when we validate our emotions to ourselves (research evidences that many physical conditions are caused by buried emotions).

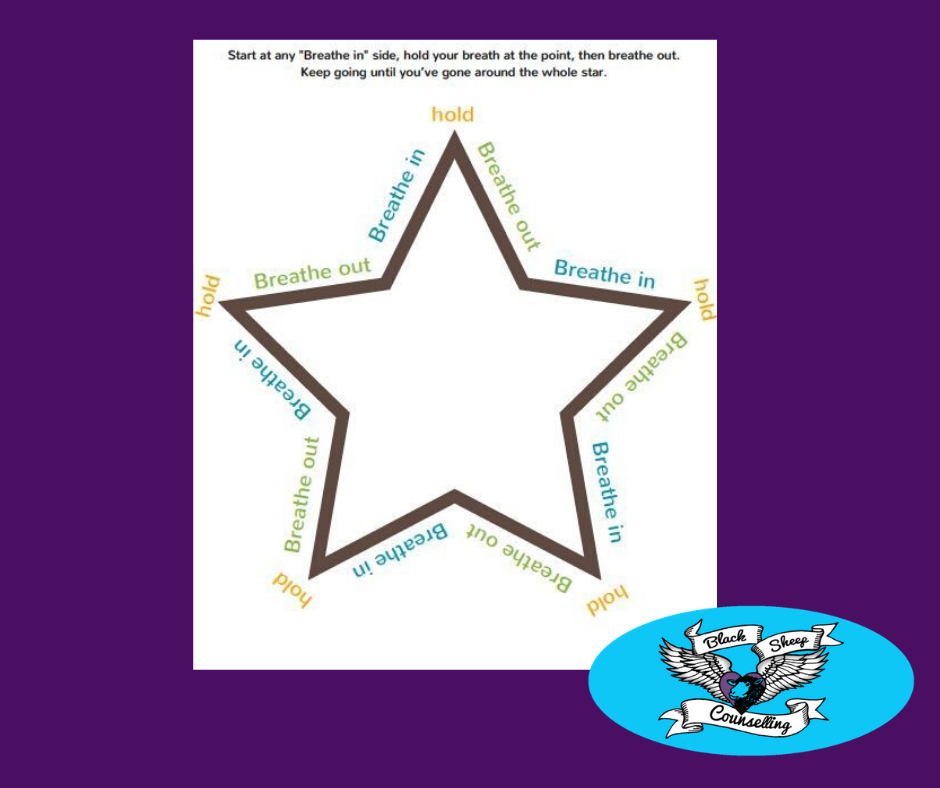

~Practice grounding and breathing. I admit, this was not something that personally came easy to me and I didn’t previously know the point in it. Now I do: filling up with air by taking deep belly breathes (diaphragmatic breathing) puts pressure on the Vagus nerve. The Vagus nerve is paramount to our well-being as it connects directly to the heart and other organs. There are lots of breathing exercises to try, so if one isn’t a fit for you, try another one. I am a fan of the 4 breathes in, 8 breathes out. For visual learners, the star breathing exercise is fun. For more on the Vagus nerve: https://blacksheepcounselling.com/2018/09/the-vagus-nerve/.

~Work towards increasing your emotional vocabulary. You sense you are “sad”. Embrace “sad” through that lens of curiosity. Is it a “weary” type of sad? Is it a “lonely” type of sad? Where does lonely-sad live in your body? Is that sensation different from weary-sad? Where does weary-sad live?

~Try a mindfulness app. Here are the 5 best free apps: https://www.mindful.org/free-mindfulness-apps-worthy-of-your-attention/

~Embrace a self-compassion practice. For more on this: https://blacksheepcounselling.com/2017/03/mindfulness-self-compassion/

~Consider complementary and alternate therapies (CAM) such as Yoga, dance, art, and music therapies, massage, Feldenkrais Method, Pilates, progressive muscle relaxation, Reiki, Qigong, Tai Chi, and others.

References:

Banich, M. T., & Compton, R. J. (2017). Cognitive neuroscience (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Bisson, J., &Andrew, M. (2007). Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2007, Issue 2. (Art No. CD003388). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub3. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.clm.nih.gov/pubmed/15846661

Briere, J. M., & Scott, C. (2015). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fosha, D. (2007). The transformative power of affect: A model for accelerated change. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Levine, P. A. (2015). Trauma and memory: Brain and body in a search for the living past – A practical guide for understanding and working with traumatic memory. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communications, and self-regulation (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2007). Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

van der Kolk, B. A., & Fisler, R. E. (1994). Childhood abuse and neglect and the loss of self-regulation. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 58(2), 145-168.