Emotional Labour

Many of the couples that I work with experience what is known as an emotional labour imbalance in their relationship. An emotional labour imbalance occurs when one individual is performing more work (emotional strain) than the other. While there is always a fluctuation of effort, power, finances, and facets of wellness (mental, emotional, physical, spiritual), in any relationship, continual imbalance can lead to the overtaxing of one person, thus leading to feelings of resentment and disconnection.

In partnerships with children, it is the mom that most commonly feels the strain of the emotional weight imbalance. Many of the female partners in my couples sessions express feeling burdened by the accumulation of seemingly endless little tasks – buying the gift for a child’s birthday, finding a suitable sitter, planning date nights, dietary concerns, registering the children’s extra-curricular activities before deadlines, remembering to pack the kids necessary supplies to take to school on any given day, laundry, playing nurse-maid to various family members, grocery shopping, setting up counselling appointments, making reservations, and often playing therapist to their partner regarding their stressors at work. This is especially taxing if the mom is also holding down a job of her own.

Managing the endless list of menial tasks can add up to one big suck-fest. With many of the couples I see clinically, this emotional labour imbalance almost always comes up. Sometimes it is addressed as “_________[my partner] is always nagging me” and from the partner “I don’t want to be a nag” [so I often do everything myself]. Other times the non-emotionally laboured partner will state “just tell me what you need me to do!”. The emotionally laboured partner states this is what is problematic for them: they don’t want to micromanage – they desire a partner with awareness who takes initiative without being told. And thus, resentment builds. There is a societal assumption that women are better able to feel, manage, and express themselves emotionally better than men. This is not a universal truth…especially when it comes to this stuff.

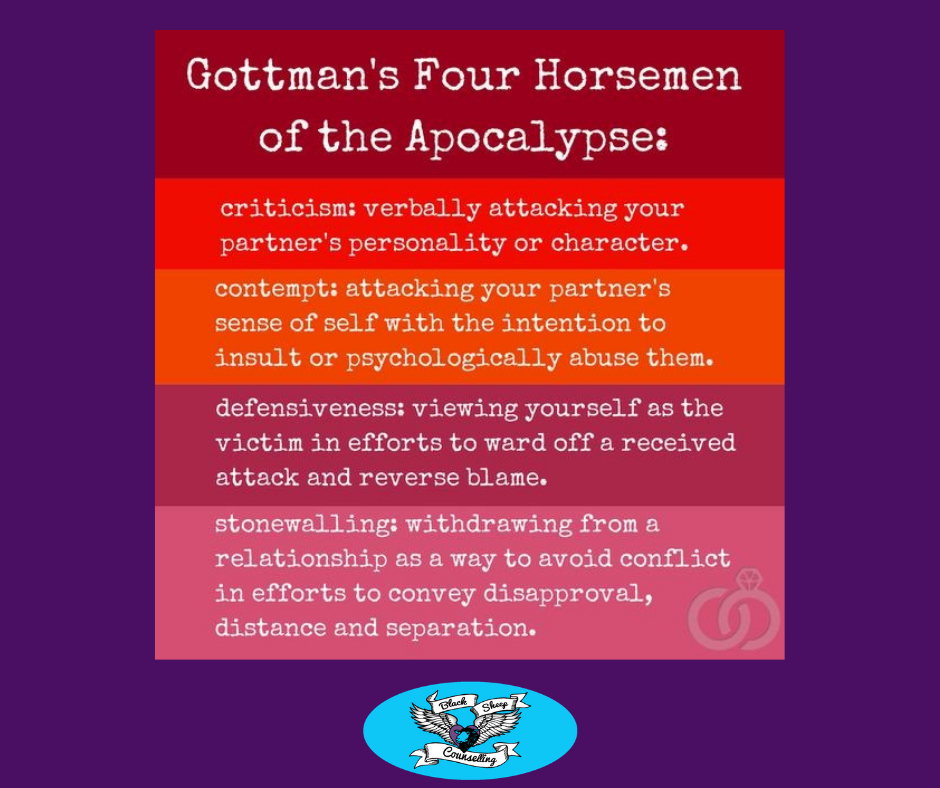

In household and family management there will always be sucky tasks that need to be done. When one partner doesn’t step up and do some of those tasks, an assumption is often made. Assumptions are rarely positive…and rarely accurate, as it turns out. Assumptions often sound like “I feel like I/the family don’t matter to you”. Frustration ensues. As do the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Gottman Method).

The Four Horsemen are:

When people engage in the Four Horsemen it predicts the demise of a relationship with 93% accuracy. Contempt is the number one predictor of relationship failure. Contempt is any open sign of disrespect toward another. Contempt often involves comments that aim to take the other person down a notch, as well as direct insults. Contempt is also seen in indirect and veiled forms, such as rolling of the eyes and couching insults within “humour.”

Let’s face it: most of us have experienced the Four Horsemen. We are human. And as human beings we get our feelings hurt and we feel the need to defend and protect ourselves.

So, how do we address the emotional imbalance stuff and resist moving into the Four Horsemen?

~Try coming up with a common language about this. Call it “emotional weight”, “sucky tasks”, or whatever works for you. Check in regularly with one another about it. Perhaps use a scale system which can look like asking one another, “where do you think we are at this week with sucky tasks?” [on a scale of 1-10]. One partner might have their focus on the “big” stuff (like managing expensive bills) and miss the heap of tedious, time-consuming stuff. If the other partner states “this week feel like a ten!”, the other partner needs to ask specifically what they can contribute to, and the overwhelmed partner needs to be specific in what they desire. (*if you feel resentment, take that as an indicator that something within YOU needs to change – not the other person – be clear what you need). If you really are the only person who can do the current tasks (and this happens) ask the other partner to take care of dinner or something else that can take the load off for you. If the other partner cannot feasibly do anything to relieve the current load, then they can acknowledge, validate, and express appreciation – do not underestimate how valuable this is.

~Consider having a system to share the daily/weekly/monthly tasks with one another. This could be a chalkboard, whiteboard, list on the fridge, voice memos, or shared Word Doc. Cross off what has been done so the other partner/family members can move on to another task.

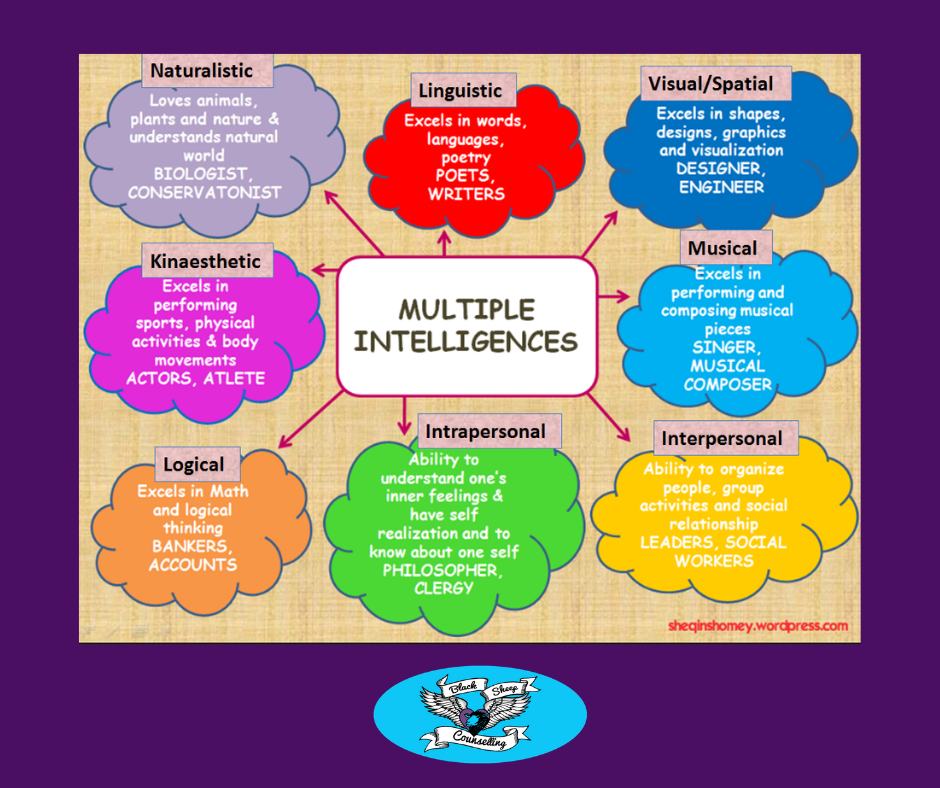

~The most successful partnerships have a foundation of understanding of one another. This does not mean they share the same worldview or agree on everything. It means there is a willingness to truly listen to one’s partner. Resist judging perceived areas of weakness. We all have areas of strength and areas of struggle. When something comes easy to us, we often overlook the fact that our personal skills and abilities are not universal. There exists 9 types of intelligence.

Chances are your partner’s skill set and types of intelligence differs from your own: try to recognize this as the strength it is, rather than get stuck in fault-finding. We all also have personal triggers. A trigger is an issue that is emotionally sensitive to us – typically something from our child, family of origin, or from a previous relationship. Try to be sensitive to your partner’s triggers ~ just like your own, they exist as a result of something painful. Resist judging or punishing your partner for their painful past experiences.

~Listen without getting defensive. Yup, easier said than done. When something you said (or didn’t say) hurts your partner’s feelings, there can be a strong impulse to interrupt with “that wasn’t my intention – you’re misunderstanding me,” even before your partner is finished talking. When this happens, both partners are usually left feeling misunderstood and invalidated. Listening without getting defensive is hard for most of us. In order to master listening without getting defensive, two things need to happen. 1) The speaker needs to voice their concerns without blame and state a positive need to prevent the listener from being emotionally flooded or responding defensively. The speaker needs to use “I” statements – “I feel ________(disregarded/underappreciated, etc.) when you do/don’t do _____________”. Avoid “you” language and using absolutes – “YOU always/YOU never” which will incite defensiveness in almost everyone. 2) The listener needs to learn to self-soothe. The Gottman Institute offers the following as effective ways to self-soothe*:

Steps to Physiological Self-Soothing:

- Think of a neutral signal that you and your partner can use in a conversation to let each other know when one of you feels flooded with emotion. This can be a word or a physical motion, e.g. “Collywobbles!” or “Hocus-pocus,” or simply raising both hands into a stop position. Come up with your own! If you choose a ridiculous signal, you may find that the very use of it helps begin to diffuse tension.

- When you have moved apart to take your break, attempt the following: imagine a place that makes you feel calm and safe. A sacred space where nothing can touch you. It may be a place you remember from childhood — a cozy corner you read in, your old bedroom, or a friend’s house. It may be a beautiful forest you explored on a trip. It may be a dreamscape. As you imagine yourself in this sanctuary, lose yourself in the peace of mind that it brings you. Meditating on a haven in your imagination can be a perfect, relaxing break from a difficult conversation.

- Practice focusing on your breath: it should be deep, regular, and even. Usually when you get flooded, you either hold your breath a lot or breathe shallowly. So, inhale and exhale naturally. As in Eastern practices – from yoga to contemplative meditation – you may find yourself calmer and more centered if you stop for a moment, and allow the noise around you to temporarily fade away.

- Tense and relax parts of your body that feel tight or uncomfortable. Feel the warmth and heaviness flow out of your limbs. Take your time. This technique is similar to a focus on breathing, but you may find one or the other preferable. Work with either of these techniques to feel your stress flow away.

We think taking a break of this sort is so important that we schedule this exercise into the conflict-resolution section of every workshop that we run. Soothing themselves makes couples better able to work on their conflicts as a team rather than as adversaries.

Think of these as starting points for the creation of an island of peace within yourself. You can return to this place again and again, whenever you like.

Your (and your partner’s) mental health play a large role in determining the health of your relationship. Don’t forget to take care of yourselves! Devote enough time and energy to self-care (getting enough sleep, nutrition, exercise, time for pursuit of your passions), and watch the frequency and intensity of fights between the two of you drop dramatically.

Remember: the ability to self-soothe is one of the most important skills you can learn. Practicing it can help you not only in romantic relationships, but in all other areas of your life.

~Write down what your partner says and note any defensiveness you are feeling. Dr. Gottman suggests writing down the specificity of what your partner says so you can review it when you are less emotionally flooded. Read it before responding to your partner. Avoid putting your interpretations or assumptions on what they said. Again, use your “I” statements when responding.

~Be mindful of love, respect, and upholding dignity. Avoid bringing up past wrongdoings and painting your partner in a negative light. Recall fond memories, shared jokes, rituals of connection, and ways your partner has demonstrated their love. Thinking about the “good stuff” will help move you away from feeling adversarial and victimized. Remembering that “hurt people hurt people” can help incite compassion for someone who may be behaving in a seemingly unloving way.

~Be curious. Anger is a secondary emotion: it is an intense reaction to an unmet need. If you are angry, what emotion is underneath that anger? If your partner is angry, what emotion might be underneath their anger? We often feel defensive when someone expresses anger, but chances are we would not if they stated to us their underlying emotion (such as: “I felt excluded at work today” or “I had an upsetting conversation with my mother today” – both of these examples incite compassion towards our loved one rather than anger or judgment). If you are feeling defensive, ask yourself why. What do you feel you need to protect? Is what your partner saying reminding you of something upsetting from the past?

~If you find what your partner is saying to be triggering, own how you are feeling and ask them to reword it. “I am feeling defensive by what you are saying. Can you please reword it so I can better understand your need and explore viable solutions?”

~If you are not in a place to truly listen, ask for a break. Taking a break is far better than saying things in the heat of the moment that are unnecessarily hurtful. Again, own your experience and state how long you need “I am taking things personally, can we take and break and reengage in 20 minutes?” In the break time, make sure to practice physiological self-soothing. If you are still not ready to reengage in the allotted time, share that with your partner and state how much longer you are needing. Taking care of yourself when you are flooded is important, but it is also important to share with your partner what you are doing, otherwise it can feel like stonewalling or incite feelings of abandonment.

Conflict between couples is inevitable and tends to fester and get worse when avoided. Embracing the courage to be vulnerable greatly enhances emotional connection and can serve as a vehicle for personal growth.

If you are struggling in your relationship, help is available.

Christine Hall, MA, RCC #120-256 Wallace Street, Nanaimo, BC V9R 5B3 christine@blacksheepcounselling.com 250-667-2228

*The Gottman Institute: https://www.gottman.com/blog/how-to-practice-self-soothing/