Adult Attachment

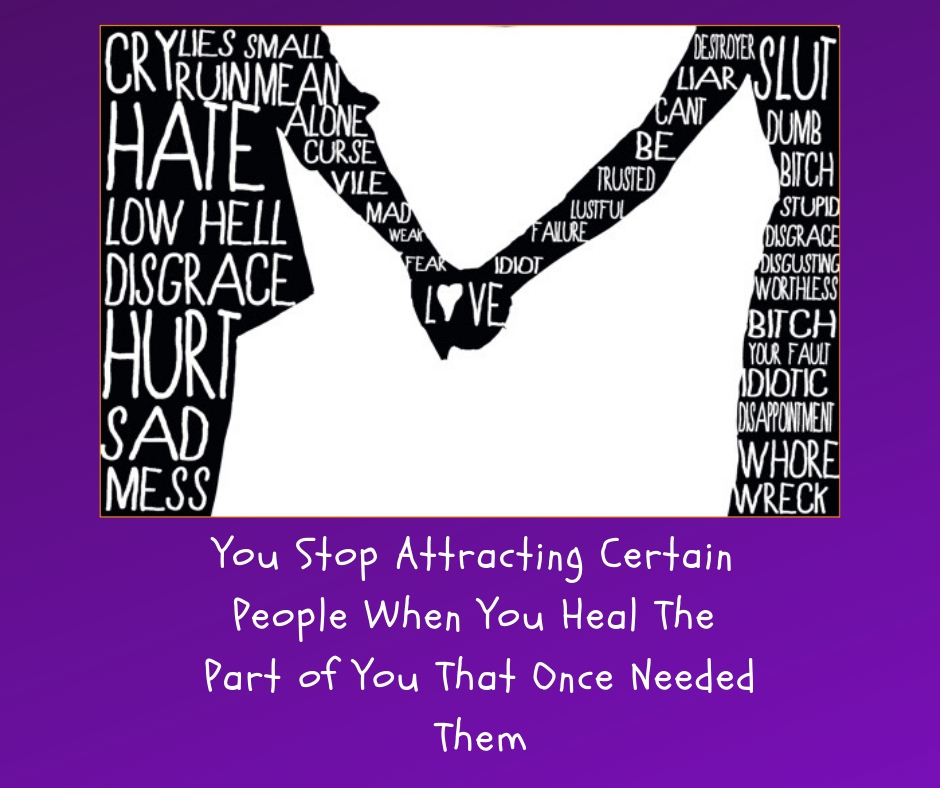

Many people experience failed relationships. Some people feel as though they experience the same relationship over and over, but with different partners (“why am I a magnet for [a certain type of] partner?!”). Some people get totally jazzed about a new relationship and then have an overwhelming desire to flee. Another may seek out partners that incite insecurities and fear of abandonment. These are some of the struggles that bring people to counselling.

Here’s some insight on what is happening:

How we are in adult relationships is mostly shaped by our interactions with parental attachment figures (the grandfather of psychology, Sigmund Freud was bang-on with his theory that our early life experiences shape adult personality). Hazan and Shaver (1987) and Feeney and Noller (1990) found that adults who were secure in their romantic relationships were more likely to recall their childhood relationships with parents as being affectionate, caring, and accepting. Securely attached partnerships exhibit interdependence: partners recognize the importance of the connection they share, while also maintaining a solid sense of Self within the relationship dynamic. Interdependent* couples (see below) chose to turn towards one another, rather than away from one another; they often intuitively *know* that vulnerability creates emotional intimacy. They also value a sense of Self that allows them and their partner to be themselves without any need to compromise who they are or their values system. Securely attached relationships support authenticity, transparency, and equality while maintaining a loving stance towards one another. Securely attached individuals might describe themselves in relationship as: “It is easy for me to get close to others, and I am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.”

Those who were lucky to experience secure attachment with their caregivers tend to have an advantage when it comes to knowing the difference between healthy and unhealthy relationships because their lived experience has gifted them with a knowingness of what safety and security *feels* like.

But what if you didn’t have optimal parenting? Some parents are abusive and neglectful. More commonplace is well-intentioned parents contending with issues like poverty, physical or mental illness, elder-care concerns, or other situations that adversely impacted the level of nurturance and attunement that were able to provide to meet your developmental needs. Such impairments in secure attachment/parental-child bonding creates what is commonly known as “insecure attachment”. There are three primary, underlying dimensions that characterize attachment styles and patterns. The first dimension is closeness, meaning the extent to which people feel comfortable being emotionally close and intimate with others. The second is dependence/avoidance, or the extent to which people feel comfortable depending on others and having partners depend on them. The third is anxiety, or the extent to which people worry their partners will abandon and reject them.

If one does not achieve the optimal “secure” attachment in early life. They develop what is known as “insecure attachment” characteristics. Insecure attachment styles can be further categorized into the following distinct presentations:

Dismissive (Avoidant) *about 25% of the population

- Emotionally distant and rejecting in an intimate relationship; keeps partner at arm’s length; partner always wanting more closeness;” “deactivates” attachment needs, feelings and behaviours.

- Equates intimacy with loss of independence; prefers autonomy to togetherness.

- Not able to depend on partner or allow partner to “lean on” them; independence is a priority.

- Communication is intellectual, not comfortable talking about emotions; avoids conflict, then explodes.

- Cool, controlled, stoic; compulsively self-sufficient; narrow emotional range; prefers to be alone.

- Good in a crisis; non-emotional, takes charge.

- Emotionally unavailable as parent; disengaged and detached; children are likely to have avoidant attachments.

Preoccupied (Anxious) *about 20% of the population

- Insecure in intimate relationships; constantly worried about rejection and abandonment; preoccupied with relationship; “hyperactivates” attachment needs and behavior.

- Needy; requires ongoing reassurance; want to “merge” with partner, which scares partner away.

- Ruminates about unresolved past issues from family-of-origin, which intrudes into present perceptions and relationships (fear, hurt, anger, rejection).

- Overly sensitive to partner’s actions and moods; takes partner’s behavior too personally.

- Highly emotional; can be argumentative, combative, angry and controlling; poor personal boundaries.

- Communication is not collaborative; unaware of own responsibility in relationship issues; blames others.

- Unpredictable and moody; connects through conflict, “stirs the pot.”

- Inconsistent attunement with own children, who are likely to be anxiously attached.

Unresolved (Disorganized; Anxiously-Avoidant; Fearful-Avoidant) *about 3-5% of the population

- Unresolved mindset and emotions; frightened by memories of prior traumas; losses from the past have not been not mourned or resolved.

- Cannot tolerate emotional closeness in a relationship; argumentative, rages, unable to regulate emotions; abusive and dysfunctional relationships recreate past patterns.

- Intrusive and frightening traumatic memories and triggers; dissociates to avoid pain; severe depression, PTSD.

- Antisocial; lack of empathy and remorse; aggressive and punitive; narcissistic, no regard for rules; substance abuse and criminality.

- Likely to maltreat own children; scripts children into past unresolved attachments; triggered into anger and fear by parent–child interaction; own children often develop disorganized attachment.

Attachment patterns are passed down from one generation to the next. Children learn their connection patterns from parents and caregivers, and they in turn teach the next generation. Your attachment history plays a crucial role in determining how you relate in adult romantic relationships, and how you relate to your children. However, it is not what happened to you as a child that matters most — it is 1) your awareness about it (we can’t change what we don’t first acknowledge) and 2) addressing it. Many individuals are able to heal their attachment wounds and create securely attached partnerships. ❤

*Interdependence means that we have not given up all our power and identity (which could create a dependent relationship situation). Interdependence is not the same as co-dependence. Co-dependence is characterized by enmeshment: a reliance on another to define a sense of Self and wellbeing. An enmeshed individual seeks their partner to meet their needs and make them feel okay about who they are. Traits of a codependent relationship include: poor/no boundaries (for more on boundaries: https://blacksheepcounselling.com/2018/07/boundaries/), blaming, projection (for more: https://blacksheepcounselling.com/2017/08/projection/), manipulation, controlling behaviours, people-pleasing behaviours, low self-esteem of one/both partners, no personal interests/goals outside of the relationship.

If you are unsure of your attachment style, try this questionnaire from Diane Poole Heller: https://dianepooleheller.com/attachment-test/

References:

Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(2), 281-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.281

Greeson, J. K. P., Briggs, E. C., Layne, C. M., Ostrowski, S. A., Kim, S., Lee, R. C., Vivrette, R. L., Pynoos, R.S., Fairbank, J.A. (2014). Traumatic childhood experiences in the 21st century: Broadening and building on the ACE studies with data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(3), 536-556. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505217

Grossman, K., Kindler, H., & Zimmerman, P. (2008). Attachment and exploration: The influence of mothers and fathers on the development of psychological security from infancy to adulthood. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., 857-897). New York, NY: Guildford Press. Harzan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Pyshcology, Vol 52(3).

Heller, L. & LaPierre, A. (2012). Healing developmental trauma: how early life trauma affects self-regulation, self-image, and the capacity for relationship. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Levy, T. (2017, May 25). Four styles of attachment. Retrieved from https://www.evergreenpsychotherapycenter.com/styles-adult-attachment/

Mate, G. (2013, July 24). The biological residue of early-life adversity. Brain Development & Learning Conference. UBC Interprofessional Education.